Day three of the European Healthcare Design 2021 Congress saw the opening keynote plenary of the COVID-19 Global Summit, a ‘conference within a conference’.

Addressing the Congress on the NHS’ experience of the pandemic, Dr Layla McCay, director of policy at NHS Confederation, explained that many of the challenges seen at the beginning of the first wave had now been addressed. “At this moment, admissions are still fairly low,” she said. “We have enough ventilators, oxygen, PPE, and intensive care beds to meet Covid needs. But we’re now at a new stage of this pandemic and that brings new challenges for the NHS.”

According to Dr McCay, the four main challenges are:

- how to manage the ongoing variants and surges of Covid-19;

- how to recover health services at the same time as enabling staff to recover and delivering the biggest ever vaccination programme while still treating people with Covid-19;

- how to manage the long-term health impacts; and

- how to sustain the innovation that occurred during the pandemic and take it forward to strengthen the healthcare system.

On the first of these areas, Dr McCay stressed the importance of the vaccination programme in reducing the number of people who will need care in hospital. There is greater knowledge now around the support that people who are unwell with Covid-19 may potentially need in regard to rehabilitation and other community services. But this is a system-wide challenge and there is uncertainty about the total extent of demand.

The NHS, she said, would need to manage the built-up demand in smart ways and increase capacity considerably. But there is no overnight fix, and making inroads on waiting lists will need investment in time, equipment, facilities and ways of working.

The long-term impact of Covid-19 encompasses a wide range of problems needing input from GPs and specialists. Dr McCay highlighted, in particular, how the younger generation have suffered in regard to their mental health and there is evidence of more people dealing with depression, anxiety and eating disorders. Added to this are wider challenges that impact on health, such as unemployment, economic instability, the impact of lockdown, domestic abuse issues, separation from one’s social support system, and anxiety bereavement – all of which, she expects, will translate into demand for health services.

But there are many positives to come out of the pandemic. “Through the NHS Reset campaign, health leaders repeatedly tell me that the innovations they had wanted to bring in for years, and which they had estimated could take a decade to implement, just happened during the pandemic to meet the need of the moment, with previous barriers falling away to help them do that,” explained Dr McCay.

One of the obvious successes has been the shift to remote consultation, increasing convenience, efficiency, and enabling a more flexible use of estates across the NHS.

Other innovations cited by Dr McCay include the virtual wards concept, the Internet of Things, enhanced use of tools such as AI-powered screening and diagnostic tools, and improvements in interoperability and data sharing. However, there is still insufficient investment in health and social care digital infrastructure, as well as concerns that a shift to digital ways of working will widen inequality gaps.

The pandemic has also driven a lot of system working, which has not only benefited patients but is particularly timely as new NHS legislation comes in. “This aims to further enable the integration of services, collaboration with the NHS and local authorities, and importantly, it aims to bring an increased focus on working together locally to achieve local outcomes, addressing health inequalities and improving community and population health, and the wider determinants of health,” said Dr McCay.

Other positive changes include how the pandemic has highlighted the urgency of place-based approaches; growing momentum around the NHS as an anchor; and the UK Government’s ‘Levelling up’ agenda, which Dr McCay described as an important framing tool for approaching population health.

And all these changes and experiences will have important implications for NHS estates. Social distancing and infection control requirements will impact the number of people who can be present in a waiting room; the flows around healthcare facilities; how equipment is disinfected and how long it takes; the operation of separate red and green areas; various types of separations; and operating across entirely different sites.

“Investments in workforce wellbeing are an important area and at the forefront of people’s minds right now,” said Dr McCay. “At the heart of the NHS is its people and supporting them is what is going to make the whole system thrive. There is a high risk of exhaustion and burnout, so how can design contribute to their rest, support and strengthening of resilience?”

Digital expansion is also ripe for innovation, but there are questions about how to shape the future of healthcare so that it works well for staff and patients from a digital perspective, as well as from an integrated perspective.

How design can help both in healthcare facilities and beyond will also be a key question to consider. “The new regulations will recognise [healthcare] increasingly as a place-based population concern,” said Dr McCay. “Design has got a key role to play in both health promotion and in the prevention of physical and mental illnesses, and I know that we all want to seize those opportunities.”

The role of the National Centre for Infectious Diseases in Singapore

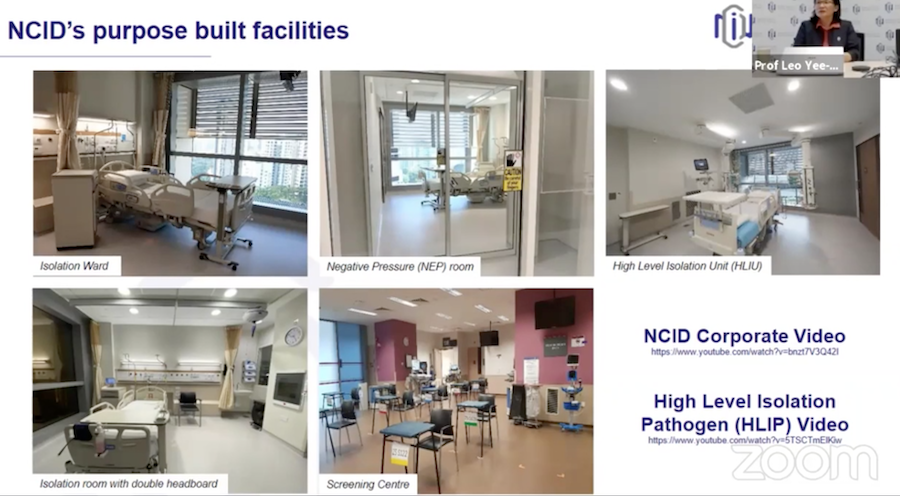

Moving from the UK to the Singaporean experience, Prof Leo Yee Sin, executive director of the National Centre for Infectious Diseases (NCID), offered delegates her perspective on how the organisation is helping direct the in the city state’s pandemic response.

The NCID, planning for which began following the 2003 SARS outbreak, was designed to strengthen Singapore’s capacity and capability in infectious diseases and outbreak-related prevention, surveillance, clinical management, outbreak readiness and response.

The NCID, planning for which began following the 2003 SARS outbreak, was designed to strengthen Singapore’s capacity and capability in infectious diseases and outbreak-related prevention, surveillance, clinical management, outbreak readiness and response.

Integrating clinical management, public health, research, training/education, and community outreach, the 330-bed purpose-built facility officially opened in September 2019 (although it had been operating for several months prior to this date) and features a full suite of medical facilities, including 17 wards (124 negative pressure rooms, 100 isolation rooms, and 64 cohort beds); two intensive care units comprising 38 beds; four high-level isolation units; two operating theatres; biosafety labs; a satellite diagnostic lab; a research lab; a screening centre, among other areas.

The building is built according to five key design principles.

“The first one is capacity and scalability,” explained Prof Leo Yee Sin. “The capacity we modelled after the SARS outbreak in 2003. At the same time, we built in some capability for us to be able to expand. We made sure the facility is capable to support the functions and role of the NCID to be able to support the entire nation.

“Convertibility is the ability to convert some of the surge capacity unused during non-outbreak periods to be usable for other reasons. The facility is also connected to a general hospital where we can tap into the multidisciplinary medical support, as well as connected to an academic centre, the Lee Kong Chian School of Medicine.

“Lastly, the most important component is safety: to make sure this building is safe for all users, healthcare providers, patients and any users who move around the building.”

Before Covid-19, the NCID first faced an outbreak of Monkeypox in May 2019. The index case presented themselves to the emergency department linked to the NCID and was immediately sent to the isolation facilities. The nearby National Public Health Laboratory received the sample and was able to carry out in-house testing, as well as an electron microscope inspection.

It took around 30 hours from receiving the case to the electron microscope findings and final diagnosis.

“This case gave us a lot of confidence to manoeuvre clinical care public health, as well as investigations, within the building itself and within a short period of time,” said Prof Leo Yee Sin, who went on to describe how Singapore’s national strategy to manage Covid-19 consists of four key pillars – enhanced surveillance; active case finding; containment; and reduced importation.

Picking up on the containment pillar, Prof Leo Yee Sin explained how contact tracing is enabled through people’s mobile phones and a downloadable app – a strategy called ‘Trace Together’.

“That basically gives us the ability to track the movement of individuals for contact tracing. We don’t track for private issues but if there is a need to utilise this to be able to look at epidemiological investigation and link up case to case,” she said.

And as part of containment, testing capacity was ramped up with the development and deployment of testing kits, supported through healthcare regulations, to ensure effective instruments were brought in to provide accurate information.

“Today, we’re able to do 70,000-80,000 cases a day in terms of testing capacity,” said the professor. “We’ve tested more than 12 million so far (as of 7 June), and it’s almost up to 2.1 million swabs per million population.

The final part of the containment strategy involves isolation and management. With the rapid identification and isolation of confirmed cases, severe cases are sent to hospitals, while those with mild symptoms and asymptomatic cases are cared for in community care facilities – large, repurposed exhibition halls with up to 20,000 beds capacity.

The molecular epidemiology is also a key strand of Singapore’s strategy, with the National Public Health Laboratory sequencing one-third of all cases in Singapore and uploading the whole genome sequence into GISAID – a global science initiative that provides access to genomic data of influenza viruses and the coronavirus responsible for Covid-19.

This platform has been used a lot, said Prof Leo Yee Sin, not only to find out whether there are variants of concern but also to enhance epidemiological investigation work.

Returning to the NCID’s integration of clinical functions as well as the epidemiology aspect, analysis and investigative work identified age as the most significant independent factor influencing severe disease, with mapping showing both the oxygen and ICU requirements for patients according to age.

Said the professor: “That information helped Singapore a lot to triage different levels of care, putting patients with high risk into the acute care setting, and younger individuals without co-morbidities, and low-risk individuals, we would take care of them in the isolation care facilities in the community.”

Clinical cases admitted to the NCID also provide opportunities to receive clinical samples and data. This has led to the setting up of the PROTECT cohort, which was pre-established in 2012 in anticipation of emerging infectious disease outbreaks. The cohort, explained the professor, supported multiple aspects of clinical research, including pathogenesis, clinical samples, diagnostics, therapeutics, planning vaccines, managing transmission, as well as socio-behavioural and communications.

This research capacity also allowed the NCID to co-ordinate national research efforts on Covid-19 and bring in other public healthcare institutions, academia, research institutions, and other stakeholders.

“That gave rise to a multiple evidence base – evidence to support how we further refine our prevention strategy, as well as treatment strategy,” explained Prof Leo Yee Sin.

She added: “Data sharing, data pulling and data analysis are key, along with the ability to share that data across multiple platforms, including global platforms – so networking is one of the key areas we’re looking at to connect up with the regions and our international partners to do research and innovation work. Communication and information sharing are also one of the very important areas . . . to make sure we can beef up community resilience and enable to mobilise our communities in the prevention strategies against Covid-19.”

And with nations at different stages of progress in their vaccination programmes, she concluded by underlining how no nation is safe from Covid-19 until all nations are safe.