The UK and many other developed nations are facing myriad challenges in strengthening resilience within our healthcare systems, but there are opportunities to seize that can help us in this quest, such as investment in technology and the learning of new skills by both staff and patients. This was how Dr Jennifer Dixon, chief executive of the Health Foundation, in the UK framed her opening keynote to the European Healthcare Design Congress 2023 at the Royal College of Physicians, London last week.

Referencing the famous US economist John Kenneth Galbraith, who once remarked that “the only function of economic forecasting is to make astrology look respectable”, Dixon nevertheless pointed to the current data and projections indicating the difficulties ahead for health, health systems and wider economies in much of the developed world. She noted that growth in health spending tends to mirror GDP growth, which, over the past decade, has been middling in the 2-4 per cent range. According to OECD data from March this year, the recovery from Covid-19 is looking fragile, with the UK near the bottom of the growth table, at -0.2 per cent this year and forecast to rise to 0.9 per cent in 2024. The picture internationally during the pre-pandemic period, 2013-20, has been somewhat mixed, ranging from 0.6 per cent in Finland to over 6 and 7 per cent in Eastern European countries.

Since the mid-1950s, health spending in the UK has increased as a share of government spending. Other areas, such as education and defence, have been squeezed, to the point at which healthcare now represents 38 per cent of all public services spending, said Dixon.

“In the UK, health has had the lion’s share, even though we haven’t invested huge amounts compared with other countries,” she remarked. “To feed our healthcare ‘habit’, we’ve had to squeeze on other areas. So, the question is, as in other countries, ‘how long can we keep doing that if economic growth is limp, if taxes are rising, and if we’re not prepared to take on more fiscal debt?’”

With average real-terms growth in government spending on health at about 3.9 per cent, on average, since the early 1980s, the “measly 0.1 per cent real-terms growth pencilled in at the last Spring Budget” shows the difficult situation in which the UK finds itself. Moreover, the UK Government spends 21 per cent less on health per head than France, and 39 per cent less than Germany. “Over a period of ten years, that’s a lot – and it shows,” said Dixon.

“Can we continue in this way if we want to live within our means in the future?” she asked, adding that social care is the elephant in the room that can no longer be ignored. “Despite the huge increase in over-70s and those over-70s with multiple long-term conditions, social care funding has remained flat – and, in fact, fell during the austerity years post the financial crash. There are lots of older people going without and, as a result, they’re revolving into healthcare services in a bigger way.”

Demographics and workforce

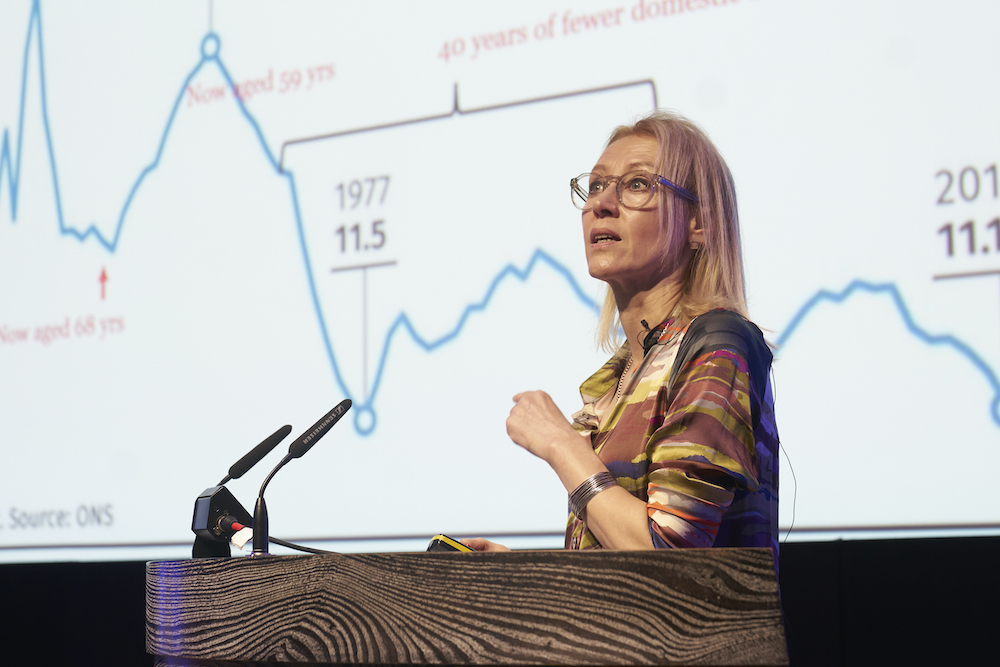

Indeed, demography is a further challenge that is already and will continue to place ever-growing strain on our health systems. With the birth rate dropping in many European countries – with Italy experiencing one of the most acute crises – there are inevitably going to be fewer workers in the future to support older people and generate the economic growth needed to pay for health services. The future for the UK, said Dixon, is likely to follow Japan, the demographics of which are changing rapidly, “creating a top-heavy pyramid with more older people than younger people”.

Stalling life expectancy across most of the globe in the past decade is also contributing to “a changing picture of the overall fabric of health”, noted Dixon. And according to the Health Foundation’s own analysis, there are now “a lot of workers in the [lower-income deciles] who are getting sick and collecting chronic illnesses in their 50s and 60s. They are working age, so we’ve got to do something there.”

Throwing other issues, such as obesity and mental health into the mix, and the growing numbers of economically inactive workers on long-term sick leave is a disturbing trend.

These issues are also manifesting in global workforce shortages and strike action, generally about pay, workload, and quality of care. There are nurse shortages in certain areas, particularly in community health nurses; mental health nurses; health visitors; and learning and disability nurses.

A final challenge is around the green agenda, and Dixon sees this as a more positive story, particularly in addressing the NHS’ direct carbon footprint.

Planning priorities

In planning for the future, these challenges and others will need to be addressed. To mitigate limited economic growth, health systems will need to boost productivity one way or another, Dixon said, and technology, shifting care out of hospital, developing new skills, and finding new sources of revenue are some of the creative ways that could be considered.

The demographic challenge will involve a shift from hospital care to community, primary and social care support, while health challenges will increasingly focus on the shift to mental health; chronic disease clusters; frailty; care co-ordination; primary care; and social care.

In addition to bringing in more workers to the healthcare sector, more domestic workers will need to be trained up with new skills, but technology and AI is seen as a “big hope” for improving workforce flexibility and productivity. Patients, too, will need to take on greater control and responsibility for their own health, along with growing self- and home management of care.

Another emerging area is “liquid health”, where single blood tests and health checks could be used to identify whether someone is at risk of developing a range of diseases. In the home, wellness and independent living space, risk management will be a far bigger constituent, noted Dixon, who added: “This will be fuelled partly by genomics risk prediction and advice, and risk mitigation for a lot of people who have risk scores. Big tech will be in there, as well as wellness firms, life management companies, chronic disease management companies, the voluntary sector, and peer support networks.”

For policymakers, the future needs to focus on long-term investment; less ideology and whim, and more coherent and evidence-based strategies; experimentation of game-changing technology with rapid evaluation; and building new skills among staff and patients.

Finally, she pointed to recent research on six different types of health system that showed that no broad type of healthcare system performs systematically better than another in improving the population health status in a cost-effective manner.

From this, she ascertained that the lesson for politicians is to “work with what you’ve got and don’t think there is a nirvana across the street”.